Testing is indicated in all people in the priority populations described in this section. Most new cases of chronic hepatitis B infection diagnosed in Australia occur in people from CALD backgrounds. Testing people born in countries with intermediate and high prevalence of HBV, including new arrivals to Australia is a crucial part of Australia’s public health response to HBV. Section 3.1 and Figure 1 identify populations that are at greater risk of infection.

It is recommended that an individual’s risk of HBV infection should inform the decision to perform an HBV test. In appropriate clinical circumstances, the absence of a declared risk should not preclude HBV testing. Clinical suspicion of HBV infection may occur in the context of:

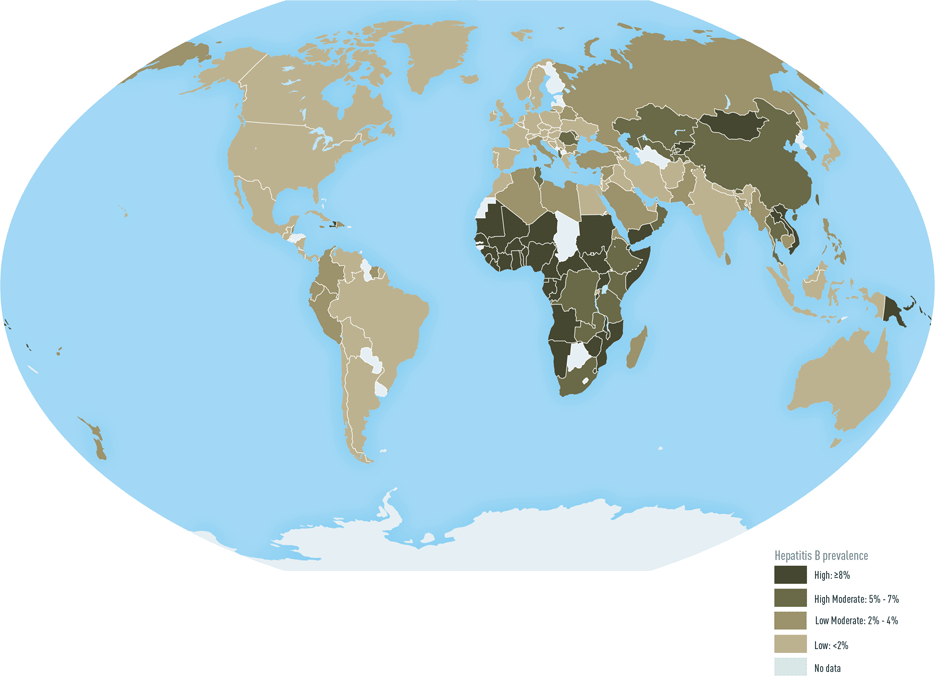

- birth in an intermediate or high prevalence country (see Figure 1)

- being an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person

- children of women who are HBsAg positive

- unvaccinated adults at higher risk of infection (see Priority populations for HBV testing)

- individual or family history of chronic liver disease or liver cirrhosis

- individual or family history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

- evaluation of abnormal liver function tests

- acute hepatitis

- family, sexual or household contact with a person known or suspected to have hepatitis B.

Other situations where HBV testing may be indicated:

- pregnant women or women contemplating pregnancy (see section 8.1)

- healthcare workers who perform or may be expected to perform EPPs. Healthcare workers must take reasonable steps to know their hepatitis B , HIV and hepatitis C status

- contact tracing where exposure to blood or body fluids of a person with the infection is documented

- diagnosis of another infection with shared mode of acquisition, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) or HIV

- a person who reports a reactive HBV result from a test not licensed in Australia;

- on the diagnosis of other conditions that may be caused by HBV infection e.g. glomerulonephritis, vasculitis

- a person who requests an HBV test in the absence of declared risk factors – a small number of individuals request an HBV test but choose not to disclose their risk factors. An individual’s choice not to declare risk factors should be recognised and it is recommended that HBV testing be offered.

|

People from priority CALD communities a, b See Figure 1 below. Please note indigenous populations in these countries often have a higher prevalence.

|

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples a, b |

|

Healthcare workers |

|

Pregnant women |

|

All patients before to undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy (due to risk of reactivation) |

|

Unvaccinated adults at higher risk of infection

|

a. If HBsAg-positive persons are found in the first generation, subsequent generations should be tested;

b. Those who are seronegative should receive hepatitis B vaccine. Vaccine is not funded for all at-risk groups and cost may be a barrier to vaccine uptake. Some jurisdictions provide vaccine free of charge for certain at-risk groups.18 Check with the relevant State or Territory health department for details.

Figure 1: Geographic distribution of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection23

For multiple countries, estimates of prevalence of HBsAg, a marker of chronic HBV infection, are based on limited data and might not reflect current prevalence in countries that have implemented childhood hepatitis B vaccination. In addition, HBsAg prevalence might vary within countries by subpopulation and locality. HBsAg prevalence is shifting in many endemic countries which have adopted universal infant vaccination. China, for example, is now an intermediate prevalence country with the age-adjusted prevalence of hepatitis B dropping from 9.8% in 1992 to 7.2% in 2009.24

People from priority culturally and linguistically diverse communities

The term CALD communities refers to individuals and their families who were born in, or born to parents, who came from overseas countries or speak different languages. Many of these countries have intermediate (2-7%) to high (≥ 8%) prevalence of HBV infection (see section 9.0). Priority CALD communities may include first and subsequent generations who may have been exposed through perinatal and horizontal transmission in Australia before the start of HBV screening during pregnancy and universal neonatal vaccination.

Most people living with chronic hepatitis B in Australia were born overseas, particularly in the Asia Pacific region, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.25 The Victorian Hepatitis B Serosurvey found a strong association between the proportion of residents born overseas in any local government area and HBV prevalence.26 A recent Australian study has found that women from high-prevalence HBV countries now living in Australia have comparable rates of infection to those of their countries of birth.27

It is recommended that all adults from priority CALD communities be tested once for HBsAg, anti‑HBc and anti-HBs to establish whether they have chronic hepatitis B, are immune through past infection or vaccination, or are susceptible to infection. Vaccination should be encouraged for those without immunity who are susceptible or at risk of infection. The purpose and implications of the test should be clearly explained before testing (see section 4.0), with the assistance of accredited interpreters or multilingual health workers as needed (see section 9.4). The result should be appropriately conveyed to the patient (see section 5.0) and documented clearly in the patient summary.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people consist of approximately 3.3% of the Australian population,28 but are estimated to represent 11% of people living with chronic hepatitis B (see Section 10.0). Estimates of prevalence in 2000 vary from approximately 2% of urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations to 8% for rural Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, with prevalence likely to be even higher in remote communities.29 More than one in five of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people live in remote or very remote areas.30 There are higher rates of death from liver-related causes in the Indigenous population compared with non-indigenous Australians,31 linked to HBV infection. The majority of cases of chronic hepatitis B in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population are believed to have been acquired by perinatal transmission at birth, or infection in early childhood, increasing the likelihood of unknown long-term infection and long term complications.32 Clinicians should stress that perinatal and early childhood exposures have been the primary routes of exposure for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Hepatitis B vaccine was introduced in many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in the mid-1980s to early 1990s, with catch-up hepatitis B vaccination programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and adolescents in the late 1990s, or earlier in some jurisdictions.11 There is some evidence of early vaccination program failure, thought to be due to limited program roll-out and imperfect adherence to vaccine storage/refrigeration (cold-chain) guidelines.33 Cold-chain guidelines were revised and improved in 2005.11

All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be tested once in adulthood for HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs to establish whether they have chronic hepatitis B, are immune through past infection, or are susceptible to infectiona. Vaccination should be discussed with those without immunity who are remaining at high risk.11 The purpose and implications of the test should be clearly explained before testing (see section 4.0), with the assistance of Aboriginal health workers, as needed. The result should be appropriately conveyed to the patient (see section 5.0) and documented clearly in the patient summary.

a These recommendations should take into account local epidemiology, historical vaccination program uptake and local policy.

Healthcare workers - Transmission and infection control in healthcare settings

HBV testing of healthcare workers and students exposed to clinical settings should be conducted in accordance with the general principles set out in this Policy with regard to privacy, confidentiality and access to appropriate healthcare and support services (see section 7.0).

Health-care workers who test positive for HBV DNA are permitted to perform EPPs if they have a viral load below 200 International Units (IU)/mL and meet the criteria set out in detail within the new Communicable Diseases Network Australia Guidelines (https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-cdna-bloodborne.htm).8 They should be encouraged and supported to undergo regular testing.

Testing for all blood borne viruses should be undertaken for healthcare workers following occupational exposure to blood or body substances, for example through needle stick injury, however, healthcare workers with immunity to hepatitis B do not need to be tested for hepatitis B after occupational exposure. Principles of informed consent (see section 4.0) and conveying a test result (see section 5.0) should be conducted with both the source of the occupational exposure and the recipient. Where patients are involved in occupational exposures, their informed consent to be tested must be sought (see section 1.4.2 for exceptions).

Pregnant women and children born to mothers who are HBV DNA or HBsAg positive.

Screening pregnant women for hepatitis B is an important strategy for reducing mother-to-child transmission (see section 8.0). Universal hepatitis B vaccination is available for all newborns. For those mothers positive for HBsAg, the timely administration of hepatitis B vaccination and hepatitis B immunoglobulin to the infant within 12 hours of birth will prevent the majority of mother-to-child transmission. Despite this immunotherapy, mother-to-child transmission can still occur in up to 10% of vaccinated infants when there is a high maternal viral load (HBV DNA >200,000 or log10 5.3 IU/mL). Antiviral prophylaxis given at 28-30 weeks can further reduce the risk of transmission.

All patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy

Patients who are undergoing any sort of chemotherapy, high dose or prolonged oral steroid therapy (e.g. more than 20mg/day of prednisolone or equivalent for more than 2 weeks) or significant immunosuppressive therapy should be tested for HBV infection.

Patients with chronic hepatitis B (HBsAg positive) are at risk of a serious and sometimes life-threatening flare of their disease, often occurring after chemotherapy has finished. All HBsAg-positive patients should therefore receive prophylaxis with antiviral therapy starting at the same time or as soon as possible after the start of chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.

Patients undergoing B cell depleting, B cell active, anti-CD20 (e.g. rituximab) therapy or haematopoietic stem cell transplantation are at particularly high risk of HBV reactivation. If these patients have serology suggestive of prior exposure to HBV (anti-HBc positive) including the high risk subgroup occult HBV (low level but detectable HBV DNA), they should be given antiviral prophylaxis for the duration of their treatment and for 18-24 months afterwards.

Partners and other household and intimate contacts of people who have acute or chronic hepatitis B infection

Unvaccinated individuals who have frequent and prolonged contact with a person with HBV infection have a higher risk of acquiring hepatitis B. The virus can be transmitted by blood through sharing personal or sharp objects such as razors, toothbrushes, earrings and nail clippers; it cannot be transmitted by casual contact through kissing, touching, sharing food or utensils. Because hepatitis B has the potential, in the right environmental conditions, to survive for at least 7 days on surfaces and objects contaminated with traces of blood, these objects can remain infectious for a long time after their use by a person with HBV infection. Child-to-child transmission, through everyday occurrences such as cuts, bites, abrasions, skin sores and scratches, has been documented.

When an individual with hepatitis B infection is identified, close contacts including household, family and intimate contacts, including all children, should be offered testing for HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc. Those without immunity should be vaccinated.11 Post-vaccination serological testing 4 to 8 weeks after completion of the primary course is recommended (anti-HBs). Non-immune household members should have repeat testing for HBsAg after 3 months. For further information please see The Australian Immunisation Handbook.11

People with a history of injecting drug use

In 2011, the estimated prevalence of hepatitis B among people who inject drugs was 4%.1 Historically, up to 50% of people who have injected drugs have serological markers of HBV infection, and PWID continue to be a population at greater risk of HBV infection given the significant barriers to accessing health services including HBV testing, vaccination and treatment.

Access to free hepatitis B vaccination for people who inject drugs is not consistent across Australian jurisdictions.22 In this context, it is critical that testing is conducted in an appropriate and non-judgemental setting to assist people with a history of injecting drug use through the testing and diagnosis process. How testing is carried out will have a profound effect on the person’s understanding of their condition and their likelihood of future engagement with the health system. A supportive environment includes understanding the current relevance of injecting drug use in the person’s life. Peer education and support may optimise testing uptake and is recommended where these resources are available. Staff in specialist and primary healthcare services should be mindful of issues relating to illicit drug use, harm reduction, addressing stigma and discrimination and managing vein care issues. Hepatitis B vaccination should be offered if testing reveals neither immunity nor current infection.11

As people with a history of injecting drug use are also at increased likelihood of having acquired HCV or HIV infection, it is recommended that testing for these infections be considered (see section 2.1).

Men who have sex with men

Historically, unvaccinated men who have sex with men (MSM) had a prevalence of past or current HBV infection of approximately 38%234 although more recent estimates are substantially lower.29 As these men commonly acquire the infection in adulthood, most MSM will clear acute HBV infection, while a small percentage of them remain HBsAg positive. Despite their increased risk of HBV infection, uptake of vaccination remains suboptimal.24 MSM should be tested for HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc (see section 2.2). It is recommended that hepatitis B vaccination be offered if testing reveals neither immunity nor current infection.11

Knowledge of hepatitis B status is particularly important in MSM considering pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV as on demand use of PrEP is contraindicated in people with chronic hepatitis B infectionwith daily PrEP the only regimen that is recommended for people living with chronic hepatitis B. see ASHM PrEP guidelines

People in custodial settings or who have ever been in custodial settings

Imprisonment is an independent risk factor for hepatitis B transmission and a history of ever being in custodial settings is an indication to offer testing for HBV with appropriate discussion of risk and benefits (see section 4.0). People entering custodial settings have higher rates of previous hepatitis B infection compared to the general community but only around 50% of people entering custodial settings have immunity to hepatitis B. People should be screened upon entering custodial settings if their hepatitis B status is unknown. Hepatitis B vaccination should be offered if testing reveals neither immunity nor current infection.11

An overrepresentation of people from CALD backgrounds and Indigenous communities and people who inject drugs can contribute to the risk of transmission in custodial settings. The situation requires further consideration to ensure screening, treatment and care are delivered in a culturally competent and culturally safe manner.

People living with HIV or hepatitis C, or both

People with HIV infection or HCV infection or both are at a greater risk for HBV infection because of shared transmission routes. Routine screening and immunisation are recommended for all people living with HIV or HCV to prevent primary HBV infection. Double dosing of hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for people living with HIV, and booster vaccination every 6-12 months as dictated by anti-HBs titres.11 For further information, refer to the Australian Immunisation Handbook.11

Patients undergoing dialysis

The frequency of HBV infection is higher in dialysis patients than in the general population because of their potential greater exposure to blood, frequent transfusions and sharing of dialysis equipment, reduced response to vaccination, and reduced durability of vaccine-derived immunity. It is recommended that all people receiving renal dialysis have hepatitis B vaccination. Vaccination is strongly recommended for patients with chronic kidney disease, dialysis-dependent or not, who are candidates for kidney transplantation. Patients should be tested every 6 months for HBsAg/anti-HBs.36 Double dosing of hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for people receiving dialysis, and booster vaccination every 6-12 months as dictated by anti-HBs titres.11 For further information please see The Australian Immunisation Handbook.11

Sex workers

Sex workers are at an increased risk of HBV infection, particularly if engaging in unprotected sex. Hepatitis B vaccination should be offered if testing reveals neither immunity nor current infection.11