A range of serological and nucleic acid tests (NATs) are used for donor screening and diagnostic testing.

Table 1. Technology, purpose, and categorisation of assays used for hepatitis B testing.

|

Marker |

Abbreviations |

Purpose or uses |

Technology |

|

Hepatitis B surface antigen (qualitative) |

HBsAg |

Donor screening – screening of blood and tissue donations |

Immunoassay |

|

Diagnostic testing* |

Immunoassay |

||

|

Hepatitis B surface antigen neutralisation |

Confirming the presence of HBsAg |

Immunoassay |

|

|

Hepatitis B surface antigen (quantitative) |

HBsAg |

Monitoring of therapy |

Immunoassay |

|

Hepatitis B surface antibody |

anti-HBs or HBsAb |

Determining protective immunity** |

Immunoassay |

|

Hepatitis B core total antibody |

anti-HBc total or HBcAb total |

Part of strategy to determine exposure to HBV |

Immunoassay |

|

IgM to hepatitis B core antigen |

anti-HBc IgM or HBc IgM |

Part of strategy to diagnose acute hepatitis B infection |

Immunoassay |

|

Hepatitis B e antigen |

HBeAg |

Determining infectivity of a person with HBV infection and phase of the infection for clinical management |

Immunoassay |

|

Hepatitis B e antibody |

Anti-HBe or HBeAb |

Determining seroconversion from hepatitis B e antigen and phase of the infection for clinical management |

Immunoassay |

|

Hepatitis B virus DNA (qualitative) |

HBV DNA |

Donor screening – screening of blood and tissue donations |

NAT |

|

Hepatitis B DNA Viral Load (quantitative) |

HBV DNA VL |

Monitoring and management- quantifies virus for clinical management |

Quantitative NAT (viral load) |

|

Confirm the presence of circulating HBV |

|||

|

Determining HBV reactivation |

|||

|

Hepatitis B genotype / mutation conferring resistance*** |

|

Characterising virus for clinical management |

Sequencing or Line probe assay |

NAT: nucleic acid test IgM: immunoglobulin M

*During infection an excess of HBsAg is secreted into the blood. The immunoassay for HBsAg has proven to be the primary diagnostic test for HBV infection because its presence indicates active infection, which may be acute or chronic. Resolution of acute infection is marked by loss of HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBs, while the persistence of HBsAg for longer than 6 months defines chronic infection. A transient HBsAg positivity may be detected for several days post-vaccination in adults and up to 2 weeks in neonates and immunosuppressed patients.10

** Anti-HBs levels fall over time and may become undetectable in people vaccinated several years ago or in those who have cleared the virus. In the setting of normal immune function, these individuals are still regarded as having effective immunity. Where relevant, the detection of anti-HBc may provide evidence of past exposure when anti-HBs has become undetectable. Refer to the Australian Immunisation Handbook for further advice.11 People with immunosuppression from any cause, including advanced HIV, renal disease, chemotherapy or immune deficiency, may be at risk of HBV infection despite previous HBV vaccination if their anti-HBs titre is <10 mIU/mL11 Testing for infection would be as for diagnosis of acute HBV infection, although HBV DNA may be the preferred first investigation due to poor antibody responses.

***Hepatitis B genotype/mutation conferring resistance testing is not rebatable on the Medicare Benefit Scheme and a fee may be payable.

Tests for HBV must comply with the regulatory framework for in-vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVDs)12 under the Therapeutic Goods Act 198913 and subordinate legislation. Testing in laboratories must comply with standards specified by the National Association of Testing Authorities (NATA)14 and the National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council (NPAAC).15

Donor screening

It is mandatory for Australian laboratories screening blood or tissue before transfusion or transplantation to test the donor’s serum or plasma for the presence of HBsAg and HBV DNA.16 Blood donors and donors of most tissues are screened for the presence of HBV DNA using a multiplex NAT assay that detects human immunodeficieny virus-1 (HIV-1) RNA, hepatitis C (HCV) RNA and HBV DNA. Blood and tissue donor screening can only be performed by laboratories accredited by Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) to the code of good manufacturing practice. IVDs used for donor screening must be intended for that purpose and be included on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) as a Class 4 IVD.

Diagnostic tests

Individuals suspected of exposure to HBV may be tested for a range of diagnostic markers depending on their clinical history, symptoms and previous test results. Examples of the common serological patterns observed in acute and chronic HBV infection are shown below (see Diagnostic strategies for HBV). All assays intended by the manufacturer for the clinical diagnosis of HBV infection are Class 4 IVDs.

Common diagnostic testing strategies encompass:

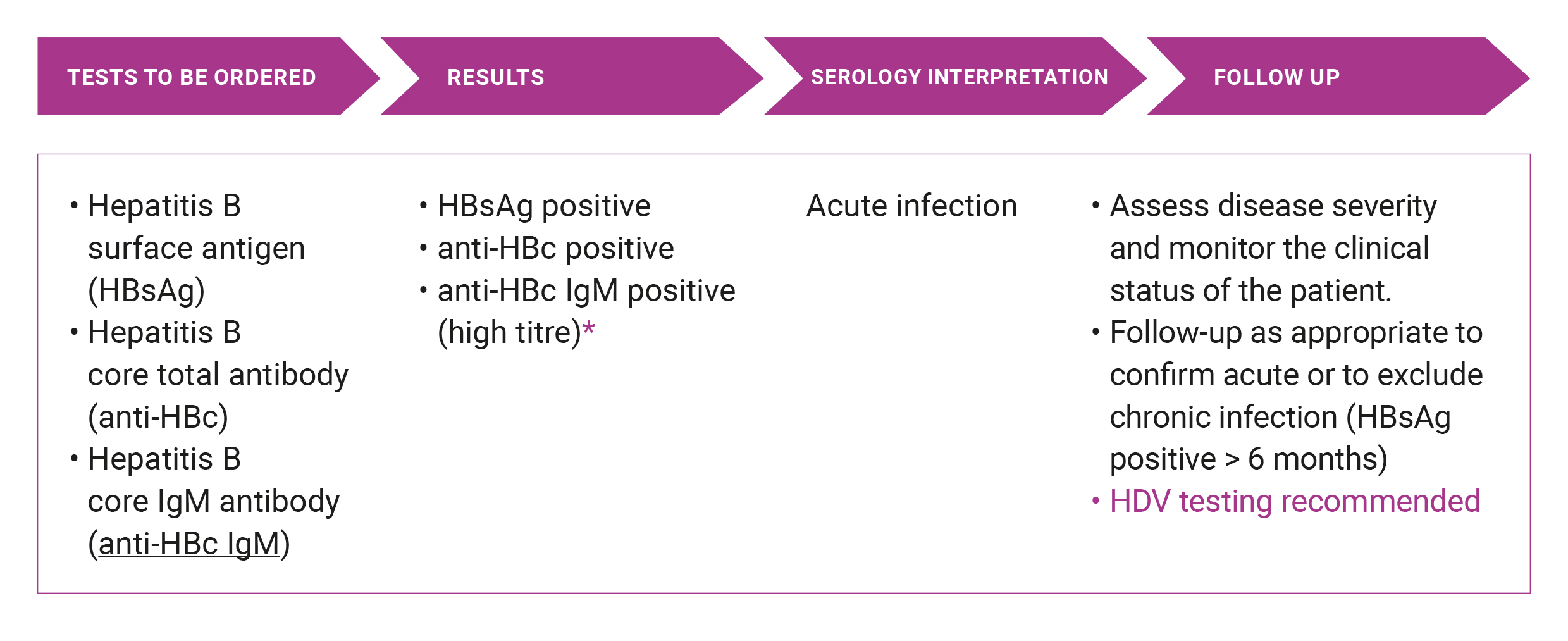

- diagnosis of acute HBV infection (5% of notifications) – HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBc IgM

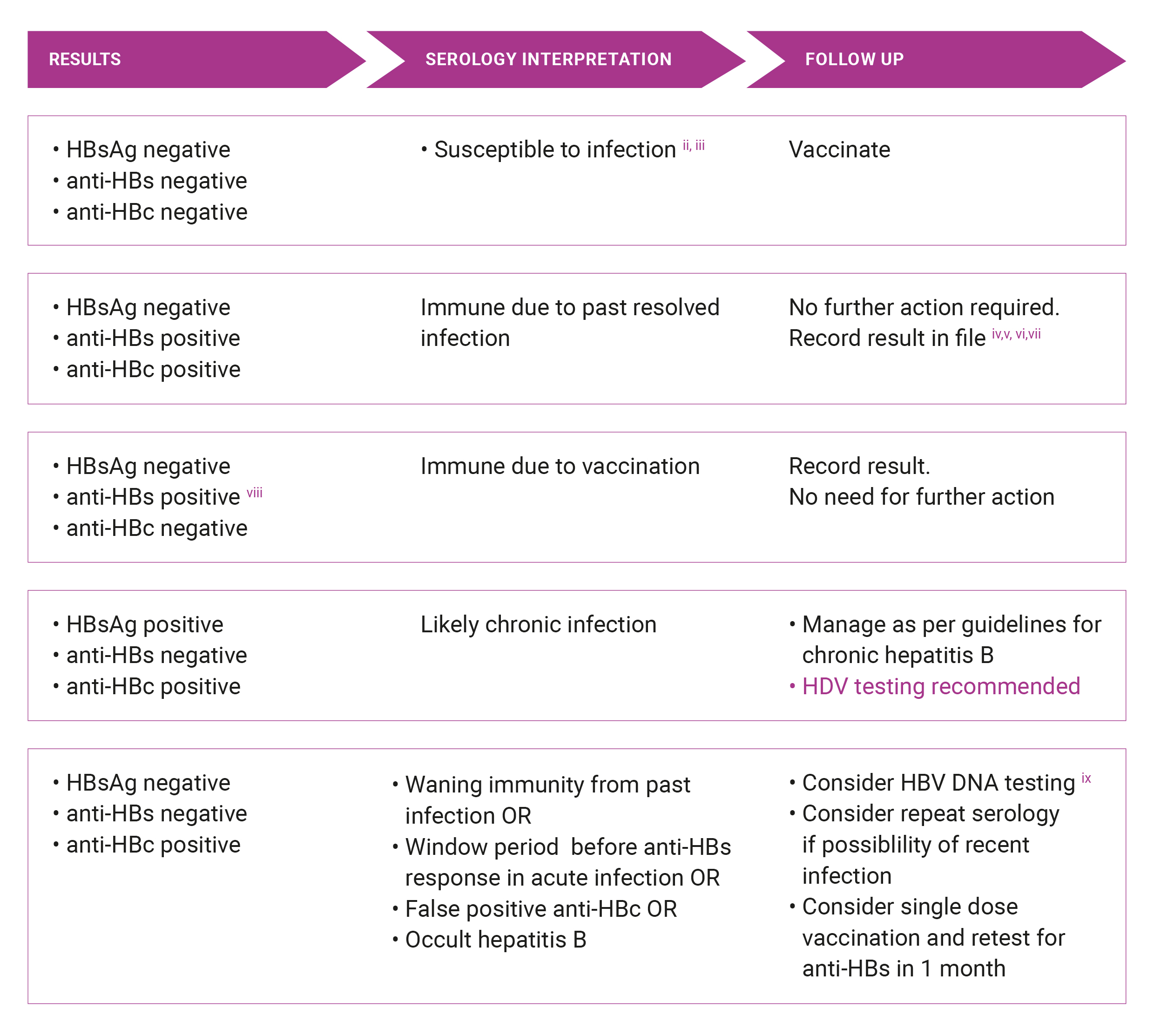

- diagnosis of chronic HBV infection – HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc

- determination of protective immunity or its absence – anti-HBs; (if anti-HBs is negative, recommend HBsAg and anti-HBc testing to exclude undiagnosed infection or distant past infection)

- antenatal – HBsAg; (if possible, also perform anti-HBs, to assess the need for vaccination)

- insurance screening– HBsAg

- investigation of degree of infectivity when HBsAg positive or the assessment of disease phase in a person with chronic hepatitis B – HBV DNA; anti-HBe, HBeAg

- monitoring of therapy – quantitative HBV DNA, HBsAg, HBeAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBe.

Benefits for these tests (Medicare Benefit Schedule (MBS) items 69475 - 69484) are only payable if the request from the referring practitioner identifies in writing that the patient is suspected of having acute or chronic hepatitis, either by use of the provisional diagnosis or relevant clinical or laboratory information. More detail on HBV testing and the MBS are presented in chapter Funding of HBV testing of this Policy or from MBS online.

Rapid Tests for Use at Point of Care

From 1 October 2020, changes to the supply of self-tests under the Therapeutic Goods (Medical Devices—Excluded Purposes) Specification 2020 will come into effect. Sponsors and manufacturers will be able to apply for inclusion of allowable self-tests in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). Individual products will be evaluated by the TGA to ensure the tests are safe and perform as intended by the manufacturer.

While there are settings where HBsAg Point of Care Test (POCT) would be useful (e.g. testing in remote communities and where there are barriers to accessing traditional healthcare), HBsAg POCT are known to have a lower analytical sensitivity compared to standard laboratory immunoassays and may be unable to detect low levels of HBsAg. Some people in the community may access self-administered HBsAg POCT kits from overseas. Therefore, when a person indicates they have received a positive or negative result from a HBsAg POCT, the restults should be confirmed by standard HBV testing in a NATA-certified diagnostic laboratory. A point of-care HBV DNA test (Cepheid Xpert HBV Viral Load assay) has recently been approved by the TGA, but the cost of this test is not rebatable through the MBS unless the patient has been shown to be HBsAg-positive.

Reference tests

The presence of HBsAg detected by screening tests must be confirmed by HBV neutralisation testing as recommended by the manufacturer’s instructions as approved by the TGA. A reagent containing anti-HBs is added to an aliquot of the positive sample and a reduction in reading (signal strength) is observed in the neutralized sample to confirm the initial positive result. HBV and hepatitis D virus (HDV) genotyping can be useful tests for epidemiology studies and for investigating transmission and are available in specialised reference laboratories. They are not rebatable through the MBS.

Hepatitis D testing

HDV, also known as hepatitis delta virus) is a defective RNA virus dependent on HBsAg for its viral envelope and thus requires the presence of HBV for virion packaging and transmission. Infection with HDV can occur concurrently with an HBV infection (co-infection) or it may occur in a person with chron HBV as a superinfection. It is important to consider testing for HDV in all patients with HBV as there is evidence this co-infection is substantially under-diagnosed in Australia.17 Particular situations which should prompt testing for HDV infection include people presenting with a severe illness (suggesting superinfection), those with a flare of more stable chronic HBV (co-infection) or those from a region where HDV infection has a high prevalence. Testing for HDV initially involves anti-HDV serology (both IgM and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies can be requested). If the anti-HDV results are positive then HDV RNA should be requested. HDV RNA assays are not performed in many laboratories but HDV RNA requests can be referred to a specialist reference laboratory (note this test is not MBS rebatable).

Suspected acute HBV

* Note that anti-HBc IgM can often be detected during an exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection. HBV is a notifiable disease and a positive result should be notified to the relevant Public Health Authority.

Suspected chronic HBVi

i. Write in lab request ‘testing for possible chronic HBV’

ii. anti-HBs levels fall over time and may become undetectable in people vaccinated years ago or in those who have cleared the virus. These individuals are still regarded as having acquired immunity. Refer to The Australian Immunisation Handbook for further advice11

iii. HBsAg is usually detected 6-12 weeks after exposure (in high-risk situations, consider post-exposure prophylaxis as appropriate)

iv. Note that there is some risk of HBV reactivation in the setting of intense immunosuppression19

v. Consider family screening and contact tracing given possible exposure risks

vi. People at risk of already having advanced liver disease or liver cancer despite resolved HBV infection, which includes people from CALD backgrounds, people who acquired HBV infection perinatally or in early childhood, and people with other risk factors for liver disease, should be referred for assessment of liver fibrosis severity and further specialist management as required

vii. Consider passive transfer in patients who recently received plasma derived products eg. IV Immunoglobulin 20, 21

viii. Lab report must either say positive or >10 mIU/mL

ix. Occult hepatitis B is defined as the presence of HBV DNA in blood or liver in the absence of HBsAg. Generally, another HBV serological marker, such as anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs are present along with low levels HBV DNA. The condition is uncommon in low prevalence countries like Australia and in the great majority of cases does not lead to progressive liver disease. Nonetheless, HBV reactivation can occur in persons on immunosuppressive therapies and transmission of HBV to blood or organ transplant recipients has been reported (Raimondo et al J Hepatol 2019 71: 397-408).

x. HBV DNA viral load is NOT rebatable in patients who are HBsAg negative

Please note: A variety of unusual test results may be found in active HBV infection and where these results conflict with standard results, the advice of a specialists should be sought to clarify the interpretation, e.g. in active infection, HBsAg and anti-HBs may co-exist.