All testing technologies for HCV must be approved by the TGA and included in the ARTG24 before their use in Australia. Inclusion in the ARTG requires pre-market evaluation of the HCV diagnostic test commensurate with the purpose for which the test will be used.

HCV antibody tests

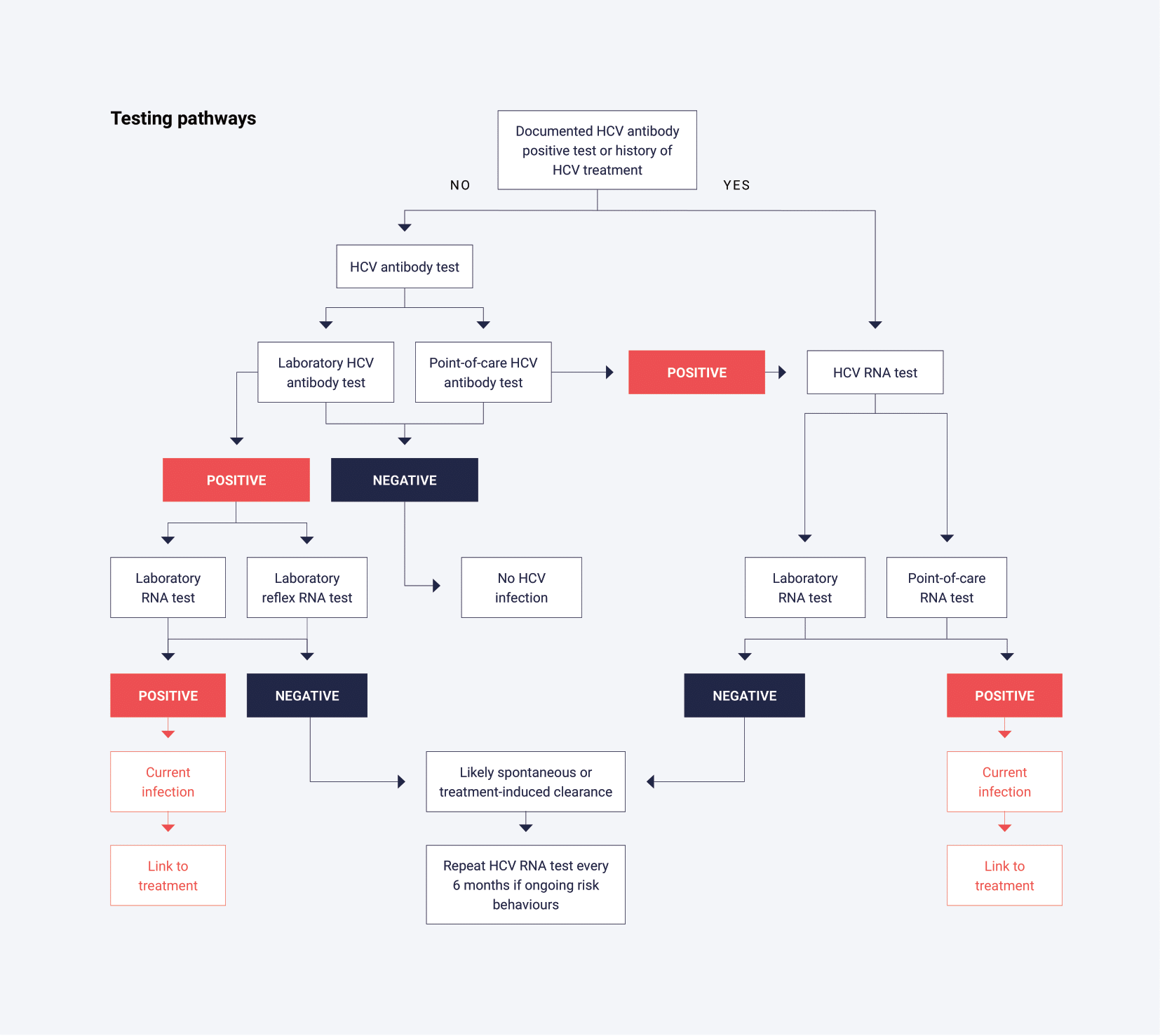

The primary tests used to determine exposure to HCV infection rely on serological detection of HCV antibodies (anti-HCV) and typically use a serum or plasma sample from venous blood. The terms HCV antibody and anti-HCV are equivalent, but in this policy HCV antibody is used throughout. Point-of-care tests are also available to determine the presence or absence of HCV antibody using whole blood from a capillary fingerstick sample. Samples yielding non-reactive results (HCV antibody negative) do not need to be further tested unless clinical considerations demand it, such as suspicion of a very recent infection due to specific risk behaviours.

The antibody seroconversion window period for HCV infection is prolonged and can vary from an average of 8 weeks up to 12 weeks.25,26 In the laboratory, confirmation of HCV antibody reactive (HCV antibody positive) samples is reliant on an alternative supplemental HCV antibody immunoassay. In place of a second confirmatory immunoassay, an HCV RNA test (also known as a nucleic acid amplification test [NAAT]), or an HCV core antigen test, not routinely available in Australia,27 can be used to ascertain whether the patient is currently infected with hepatitis C.

HCV RNA tests

A major goal of HCV testing is to detect current infection to facilitate linkage to care and treatment. Since HCV antibody assays only test for exposure to the virus, it is critical to ensure that people with a positive antibody test undergo additional testing to confirm current infection. Specifically, HCV RNA testing should be performed on all samples with positive HCV antibody results, where feasible. In the laboratory, this is typically conducted using a serum or plasma sample obtained from whole blood. Additionally, point-of-care tests are available to detect HCV RNA using whole blood from a capillary fingerstick sample.

This section provides advice on minimum standards for diagnosis and investigation of HCV infection. Lifeblood services (formerly Australian Red Cross Blood Service) across Australia have developed their own strategies for screening donations because of their unique requirements.28

Laboratory investigations are directed towards answering one or more of the following questions:

- Has the person ever had HCV infection? This finding should be determined by testing for HCV antibodies. HCV RNA testing should be performed on people that are HCV antibody positive to confirm current HCV infection. HCV antibody-positive samples which are negative for HCV RNA most likely represent past infection with clearance (resolved or cured by therapy). However, past HCV infection with viral clearance does not confer protection against re-infection.29

- Does the person have current infection? This finding is determined by testing for HCV RNA (or infrequently HCV core antigen, although it is less sensitive than HCV RNA testing). The presence of HCV RNA indicates active viral replication and current infection.

- What is the current level of viral replication? Viral load testing for HCV RNA is not required before commencing treatment and the RNA level has no bearing on treatment responses.

As such, a qualitative HCV RNA test is sufficient to determine treatment eligibility. - What is the infecting virus genotype? HCV genotyping is no longer required for treatment initiation, given the available therapies are effective against all genotypes (pangenotypic). HCV genotyping was removed from the PBS criteria on 1 April 2020. Nevertheless, if HCV genotyping is performed, it should be documented in the person’s medical history.

The NPAAC has published tiered regulatory compliance requirements for good laboratory practice30 regarding laboratory testing for HIV and HCV infections.27

Laboratories and laboratory staff are subject to professional standards established by the RCPA and international standards for medical testing.31 ISO 15189 is the international standard that specifies the requirements for quality and competence of medical laboratories under which laboratories receive NATA/RCPA accreditation.

For further information on standards for testing, see:

- NPAAC Requirements for Laboratory Testing of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)27

- ISO 15189 Standard for Medical Laboratories31

- NPAAC Requirements for Medical Pathology Services30

HCV antibody testing

In the laboratory, exposure to HCV is determined by testing for HCV antibodies in serum or plasma, collected via venous blood.

- A sample non-reactive in the screening immunoassay can be generally regarded as HCV antibody negative. If the antibody result does not match the clinical history or presentation, consider qualitative HCV RNA testing in people who are immunosuppressed, or in those suspected of acute infection prior to antibody seroconversion. Note that only one qualitative HCV RNA test can receive a Medicare rebate in a 12-month period.

A sample reactive in the screening immunoassay must be subject to a minimum of one alternative supplemental HCV antibody immunoassay, HCV RNA test or HCV core antigen test. As immunoassays do not have 100% specificity, it is important to eliminate, as much as possible, any common false reactivity between two tests that are to be used as part of a diagnostic strategy. A sample reactive in two approved immunoassays can be reported as HCV antibody positive. In place of testing with a second immunoassay, a qualitative HCV RNA or HCV core antigen test can be used to ascertain whether the person is currently infected with hepatitis C.27

HCV RNA testing

In the laboratory, current HCV infection is generally determined by a qualitative or quantitative HCV RNA test using serum or plasma collected from whole blood.

- HCV RNA will be negative in past infection with clearance (resolved infection or cured by therapy) but may also be negative in the very early period post exposure (initial 7-14 days).

- The availability of effective therapies against all HCV genotypes means that HCV genotyping is no longer required before treatment initiation to meet the PBS criteria. Nevertheless, identifying HCV genotype may be clinically useful for certain regimens when treating people with cirrhosis or who have received previous treatment. Furthermore, HCV genotyping can provide helpful information for at-risk populations where there is a high risk of re-infection. A genotype or subtype change may be able to differentiate re-infection from relapse. HCV genotype reimbursement remains on the MBS.

Laboratory-based HCV reflex testing

Laboratory-based reflex HCV RNA testing refers to a testing algorithm where people receiving testing have a single clinical encounter and a single blood sample is collected (this blood sample may be divided into two primary blood collection tubes), or a second tube collected and sent to a central laboratory for testing. Ideally, a second blood sample, specifically for HCV RNA testing, should be collected at the person’s initial visit, instead of obtaining a follow-up sample from a second visit. The availability of two blood samples also offers the advantage of having greater sample volume for other possible blood-borne virus testing. Laboratories may split a single specimen into two aliquots at the sample processing stage before HCV antibody testing, assuming the same sample type is validated for both antibody and RNA testing. This approach avoids the need for the doctor to request a follow-up sample and an associated second consultation.

If the initial test for HCV antibodies in the laboratory is positive, a reflex HCV RNA test using the second aliquot or the duplicate sample is automatically triggered. The results provided to the healthcare provider and person include both the HCV antibody result and, if positive, the HCV RNA result, eliminating the need for additional visits or specimen collections. Laboratory-based reflex testing has been shown to increase the uptake of HCV RNA testing among people who test positive for HCV antibody, potentially improving linkage to care and treatment compared to non-reflex testing.32

- When ordering an HCV antibody test, a request for HCV RNA testing (reflex testing) should be made if the sample is HCV antibody positive or discordant results are obtained from two serology tests. This request must be documented on the initial pathology form (‘HCV RNA if indicated’).

A point-of-care test is conducted at the site where clinical care is provided, with results returned to the person or caregiver on the same day. This approach allows for more timely clinical decisions and linkage to care. Point-of-care tests for HCV infection (antibody and RNA) can simplify testing algorithms, shorten time to diagnosis and increase rates of testing, linkage to care and treatment.33-35

All positive point-of-care test results should be notified to the relevant stakeholders.

Point-of-care HCV antibody and RNA tests are now available and have been approved for use in Australia by the TGA, with some conditions.11 The test needs to be performed by a laboratory accredited by NATA for HCV testing or by trained health professionals (e.g. in a community health setting) who have an established relationship with a NATA accredited laboratory. As with a central laboratory, in an off-site clinic or community healthcare setting, the TGA requires participation in quality assurance programs and healthcare workers need to be trained and deemed competent in the use of the test.

As with laboratory testing, NPAAC has published regulatory compliance requirements for HCV point-of-care testing.36

Point-of-care HCV antibody testing

Point-of-care HCV antibody testing determines exposure to HCV by detecting antibodies in whole blood collected via a capillary fingerstick sample. Where available, the use of finger-stick blood samples offers a significant advantage, avoiding the need for phlebotomy. This method is particularly beneficial in people where venous access is challenging or there is a preference to avoid phlebotomy, or phlebotomy services are unavailable.37,38 Approved point-of-care HCV antibody tests have sensitivity and specificity that are close to those of traditional commercial HCV antibody tests.39

- As with laboratory-based testing, a non-reactive point-of-care HCV antibody test can be generally regarded as HCV antibody negative. If doubt with the HCV antibody test result exists, repeat the test. Consider HCV RNA testing in people who are immunosuppressed, or in those suspected of acute infection before antibody seroconversion.

- A sample reactive with the point-of-care HCV antibody test must be tested for HCV RNA to identify current HCV infection (see below for reflex HCV RNA testing options).

- In instances where there is an invalid point-of-care HCV antibody test (i.e. no control visible), repeat testing should be performed.

Point-of-care HCV RNA testing

Point-of-care HCV RNA testing determines current HCV infection by detecting HCV RNA in whole blood, collected via a capillary fingerstick sample. The availability of point-of-care HCV RNA tests for detection of current HCV infection within one hour at the point of care has transformed the clinical management of HCV infection.37,38 Point-of-care HCV RNA testing coupled with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) HCV treatment enables diagnosis and treatment in a single visit, increases testing acceptability and reduces loss to follow-up, helping address the drop-off in the HCV care cascade. These tests show a similar sensitivity and specificity to traditional commercial HCV RNA tests.40

- As with laboratory-based testing, HCV RNA is negative in past infection with clearance (resolved infection or cured by therapy) but may also be negative in the early incubation period.

- In instances where a point-of-care quantitative HCV RNA test result is detectable but below the level of quantification, repeat testing should be performed. If the same result is obtained, a venous plasma or serum sample should be collected and sent for laboratory-based testing to confirm whether HCV RNA is present.

- In instances where there is an invalid point-of-care HCV RNA test, repeat testing should be performed (either point-of-care or laboratory-based testing).

- Point-of-care HCV RNA testing can be used for diagnosis, confirmation of cure and monitoring for HCV re-infection in people who have been successfully treated.

Clinic-based HCV reflex testing

Clinic-based HCV reflex RNA testing refers to a testing algorithm where people have a single clinical encounter. After a positive point-of-care HCV antibody test, a capillary fingerpick specimen is immediately collected for a point-of-care HCV RNA test at the clinic to detect current infection. Alternatively, a venepuncture sample could be taken and referred to a central laboratory for testing.

HCV self-testing involves a person collecting their own specimen (e.g. capillary blood from a finger prick) for HCV testing, applying it to a testing kit or device and interpreting the test result. As at March 2025, there are no devices for self-testing approved by the TGA for supply in Australia.

Some people in the community may access self-administered HCV point-of-care test (self-tests) from overseas for their personal use. The safety and performance of these devices may not have been independently assessed and verified. The World Health Organization provides recommendations and guidelines for self-testing for HCV.41

Before their availability in Australia, any new sample collection device or testing technology must be approved by the TGA. As at March 2025, there is no TGA-approved HCV test that is intended for use with self-collected samples, such as dried blood spots. However, there are various provisions for exemption, such as for a clinical trial, that allow for regulated access to unapproved devices.

Dried blood spot sampling for HIV and hepatitis C testing has been successfully used in a government-led pilot study in New South Wales (NSW) since 201642,43 under a clinical trial exemption from the TGA. NSW Health has completed a validation of dried blood spot sampling and anticipates a TGA submission during 2024-2025 to allow in-house use of dried blood spots without the need for a clinical trial exemption.

Self-sampling is when a person collects their own biological sample for HCV testing (e.g. blood from a finger prick) and after collection sends it to a laboratory for testing. Unlike HCV point-of-care testing and self-testing, the analysis of a self-collected sample is performed in the laboratory and a confirmed result is obtained.

The introduction of highly efficacious and well-tolerated therapies for the treatment of HCV infection has reduced the need for frequent on-treatment monitoring. Eligibility for treatment requires evidence of chronic infection, meaning detectable HCV antibody and a positive baseline HCV RNA (qualitative or quantitative HCV RNA test). Generally, routine on-treatment assessment of HCV RNA levels is not necessary, due to the lack of a role for response-guided therapy.

A further qualitative HCV RNA test is required to confirm sustained virological response (SVR), which is defined as an undetectable HCV RNA at 12 weeks after the end of DAA therapy (SVR12). There are now several studies that show that there is a high correlation between obtaining an SVR at 4 weeks post-treatment completion and SVR12.44,45 Therefore, opportunistic testing of HCV RNA at any time beyond 4 weeks post-treatment completion can be considered, particularly when there is concern about subsequent loss to follow-up.

People who may require more intense monitoring include those for whom adherence is a concern or where there is a high risk of re-infection, those on ribavirin-containing regimens and those with advanced liver disease (cirrhosis, portal hypertension or hepatic decompensation).

For more details on testing frequency and type, see Section 6 of the Australasian recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection: a consensus statement (2022) available at: https://www.hepcguidelines.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/hepatitis-C-virus-infection-a-consensus-statement-2022.pdf